The Times newspaper has named Dr Maurice Collins F.R.C.S. of Hair Restoration Blackrock, (HRBR), as one of ‘Britain’s Top Surgeons’. Published in a special edition of The Times Magazine (10/12/2011), the guide to the best of Britain’s surgeons was compiled in conjunction with medical specialists, professional bodies and associations who listed candidates considered to be leaders in their chosen field, based not just on academic standing but also personal qualities such as dedication, empathy and professionalism.

Louis Walsh – my £30,000 hair transplant

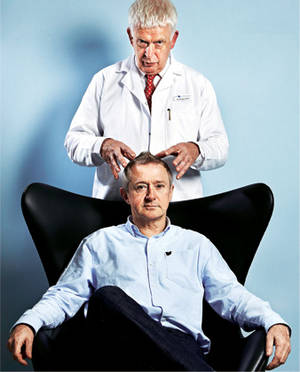

When Simon Cowell told his old sparring partner he was losing his hair, it was to Dr Maurice Collins that he turned for a solution – as James Nesbitt had done before.

When Simon Cowell told his old sparring partner he was losing his hair, it was to Dr Maurice Collins that he turned for a solution – as James Nesbitt had done before.

For some reason, it does not come as a total shock to learn that the first person to tell Louis Walsh he was thinning up top was Simon Cowell. The way Walsh tells it, you suspect his friend and former X Factor colleague actually quite enjoyed breaking the news.

“He came up to me and said, ‘You know, you’re starting to lose your hair, dear,’?” Walsh explains. “I said, ‘I am not, dear! And anyway, you’re going grey!’?” But Cowell, ever the X Factor judge delivering for-your-own-good feedback, persisted. “Darling,” he sighed. “You are. You’re losing your hair.

”It was only when Walsh, who’s now 59, glimpsed a fleeting camera shot of the back of his head that he realised Cowell was not just trying to wind him up. He re-enacts a wide-eyed gasp of horror, though he talks about it more as a professional inconvenience than as the personal catastrophe some men find it.“I could have just left it and got on with things, but with TV today, everything is in high definition, and people notice every little thing. And if you’re getting on, and you’re on TV with a lot of young people, you have to look after yourself. So I thought, ‘I don’t want a bald spot! I’m going to get this sorted.’?”

He did not have to travel far. Dublin is home to Hair Restoration Blackrock (HRBR), a private clinic based in a modern, purpose-built complex called Samson House (the Biblical allusion unsubtle but potent). This is where we meet. There is an underground car park, so that the steady flow of celebrity clients can enter the building unnoticed, and the consulting rooms have frosted-glass interior windows, for extra privacy. There are also large, gold cans of Elnett hairspray in the gents’ toilets.

The clinic is run by Dr Maurice Collins, a former ear, nose and throat specialist who has received fellowships from the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland, Edinburgh and London, and who maintains a consultation clinic on Harley Street. Collins, who performs around 200 hair transplant procedures every year, practises a method of hair restoration surgery known as Ultra Refined Follicular Unit Transplantation (URFUT). This is a process whereby thin strips of skin are taken from the back of the head (an area where, in the vast majority of male pattern baldness cases, hair will always continue to grow) with individual hair follicles attached. Each extracted follicle is surgically implanted in areas of the scalp where hair is thinning, and will produce two hairs that will continue to grow throughout the patient’s life.

“We just did 4,000 grafts on a patient today,” explains Collins, who sits beside Walsh in a private meeting room. “That’s 4,000 living organ transplants. It’s a phenomenal technical exercise when you think about it, because those hairs have to pick up a blood supply and then start growing. To put it simply, we’re moving the roses out of the back garden and into the front garden.”

Above Picture: 8 months post op. Full growth is achieved at 18 months.

The operation can take up to ten hours, costs €10 (£8.50) per follicle at HRBR and requires 18 different people – surgeons, nurses and technicians, working in shifts to extract the follicles under stereoscopic microscopes. Walsh, who underwent surgery in August, says he spent the majority of this time “reading magazines, watching DVDs” as the team worked on him (because of the tiny incisions made to the back of the scalp, there will always be some very faint residual scarring). When we meet, not long after the procedure, his £30,000 worth of transplanted hair has not yet begun to grow through. “But it will start after about six months,” says Collins. “It’d better!” squeals Walsh, grinning. “It’d better!”

Collins chuckles. He admits that the most challenging part of his job is not the complex, delicate surgery, but successfully managing the expectations of his patients. By moving existing follicles around a man’s scalp, all he is able to do is reallocate where his existing hair grows. He cannot bestow more of the stuff.

“I met one man who had no hair on the top of his head, and only a little ribbon around the side, and he literally said to me that he wanted to look like Elvis. I nearly fell off my chair.”

Walsh laughs, but Collins doesn’t. There is nothing funny, he says, about the psychological effects of hair loss. If he feels a patient has hopes for his hair that cannot be met, he simply will not operate on them.

“The first rule of surgery is ‘do no harm’, and if you have an expectation that we do not meet, then we have done you harm. It’s not a matter of meeting in the middle. They have to come down to realistic expectations, otherwise I send patients to a clinical psychologist to get help.”

He likes the fact that hair loss is a great leveller. Some patients are captains of industry “who will come over in private jets” (one businessman is travelling from Hong Kong to have treatment), some are normal people who have saved for six months just for the consultation fee. He says that there is a box of tissues in his consulting room, and it is “not a rare event” for men to weep when discussing their hopes.

“When somebody comes along and asks me and my team to look after their hair loss, they are handing over their self-esteem and self-confidence to us, and then asking us to return it intact. It sounds very dramatic and very emotive, but men bottle things up.”

One patient, he says, had just had 3,500 grafts put into his head. “And he looked in the mirror and asked, ‘Maurice, what am I going to do?’ I replied, ‘You’re going to go home.’ But he said that he couldn’t, because he hadn’t told his wife he was having the treatment. I couldn’t believe it.”

Walsh, for his part, is not a man embarrassed about his decision to opt for medical treatment. “I wanted to get the problem solved before it became a problem,” he says. “It’s like going to the doctor and getting something done for your heart before it goes. It’s called maintenance. It’s not a wig or a syrup of figs or an Irish jig. It’s just me, with my own hair, feeling better.”

It helps, he admits, that men such as Wayne Rooney and actor James Nesbitt are talking openly about their experiences.

“I saw what it had done for other people. I saw James Nesbitt before and after and I thought, ‘Hey, he looks better.’ He actually looked good… for him.”

Collins rejects the notion that men who seek treatment are acting out of simple vanity. Nobody he operates on talks about the results in terms of it making them “better looking, more attractive or more handsome”, but they do talk about increased “self-confidence and self-esteem”. When he first began working in this area, he assumed that patients would only be satisfied if they got a full head of hair back. “But that’s not actually what I found,” he concludes. “If you’re a very bald man, just being able to grow a few more hairs on your head is something that can make you very, very happy.”

James Nesbitt: ‘I don’t have to justify it. No one died, I’m happy’

James Nesbitt: ‘I don’t have to justify it. No one died, I’m happy’

James Nesbitt is still a little embarrassed about having had a hair transplant. But not as embarrassed as he used to be about going bald. “It started thinning when I was in my second year of drama school, not quite in clumps, but it was coming out. I hated it. I found it very emasculating. As a boy I had long thick hair.” Twenty years later, in his early forties, Nesbitt, who is currently filming the part of a dwarf in New Zealand in The Hobbit, decided to do something about his hair loss. “I was worried about the impact being bald would have on my career. As an actor, you’re always insecure about your next job. But I admit I partly used that as an excuse. I don’t think I lost any work for not having a full head of hair. It’s scary to admit you’re doing it out of vanity.”

An old friend, a make-up artist in Dublin called Lorraine Glynn, told Nesbitt about the work Maurice Collins was doing at the Blackrock clinic. “Lorraine had witnessed my hair going. She knew it upset me. She cajoled me into going to the clinic and came with me. Before I knew it, I’d decided to have surgery. Maurice is an extremely impressive and persuasive man. And you could pick him up by his hair. I thought: what have I got to lose?”

Nesbitt’s transplant took eight hours and involved a team of 14 medics led by Collins. “I was nervous the night before and the morning I went in, but the worst part was the anaesthetic,” recalls Nesbitt. “That was quite uncomfortable, an injection in my head. After that I was sort of semi-conscious, lying on this gurney while they took a graft of hair follicles from the back of my head and punched them into the top. I watched The Simpsons, then The Maltese Falcon, slept a bit, then The Philadelphia Story.”

Afterwards, Nesbitt was “sore, then a bit numb for a few weeks” but mostly “impatient. You’re constantly looking for something to appear, and the embarrassment is still there, thinking, ‘Am I going to make an idiot of myself? How did I become the sort of person who would do this?’ Then, after about three months, the hair began to appear and it looked great, very natural. I looked younger and healthier. There was nothing shocking or plastic about it.” It wasn’t until two years later, says Nesbitt, when he contributed a testimonial video to Collins’ website, that the media even noticed. By then he had had a second transplant, with which he is equally pleased.

Now 46, he is still a little concerned that having the procedure “sounds weird or indulgent”. Nesbitt comes from a traditional Ulster Presbyterian background, which no doubt exacerbates his worries that the amount he spent – he thinks about £20,000 – is a small fortune to many people. “If my mother had known the amount it cost, well, she couldn’t conceive of it. I know some people will think, ‘Bloody typical spoilt actor’, and when I think about it myself, I wonder how I’m the sort of fella who has a hair transplant. Then I think, ‘Ah, bollocks, I don’t have to justify it. No one died, I’m happy and getting on with my life, and I’ll be for ever grateful to Maurice for doing it.’ Whenever I run my hands through my hair I think of him.”

Publication: Times

Date: Saturday, December 10th, 2011

Author: Ben Machell

Src: www.thetimes.co.uk